Monica Morales’ Dedication to Clean Water Flows from Her Education at Oregon State

When people are passionate about what they do, it’s inspiring.

During her junior year at Oregon State University, Monica Morales (’15 M.S., Civil Engineering) applied for admission to the Civil Engineering Cooperative Program, which pairs students with paid internships. Part of the process involved being questioned by a panel of 30 engineers from participating companies. That might be intimidating to some, but not to Morales. She simply explained why she loved engineering. When she finished her interview, an engineer in the room started clapping. Then, all 30 applauded.

She told them she believed civil engineering is the key to society. “It helps satisfy Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — shelter, water, and a means to travel through buildings, pipelines, roads, and bridges,” she said. It’s possible she reminded each panelist why they loved the field.

When an engineer from the Portland Water Bureau offered an internship to Morales, he grinned and said, “You didn’t get this internship because we applauded you. You’re getting this internship because you’re a good fit.”

A Headfirst Dive into Water Engineering

Growing up, Morales had never heard of engineering. That changed the day her mother, a blackjack dealer, met a civil engineer who sat at her table. As she dealt the cards, she was struck that the man didn’t speak of his job in terms of math or algorithms, but in terms of helping people. He reminded her of Monica.

Later that night, she relayed the engineer’s passion for designing infrastructure.

Their conversation piqued her daughter’s interest in engineering. After some research, Morales decided she related most to civil engineering.

“The idea of helping people through math and science really connected with me,” she explained.

That fall, she walked into Civil Engineering 101, one of only 15 women in a class of 100. Undeterred, Morales learned about the various subspecialties in the field. By the end of the course, she wasn’t sure which way to go, but she liked the idea of working in the area of sustainability. Three years later, she walked into the Portland Water Bureau.

There, Morales learned the engineering behind the Bull Run Watershed, Portland’s primary supply of drinking water. Her team taught her how to keep the watershed clean. Soon, she was inspecting culverts and studying ways to employ renewable energy systems.

Everything clicked. Morales knew she had found her niche.

“What kept me in water was that it was ethical work. I loved the idea of getting people clean drinking water,” she said.

Back at Oregon State, she took every water resources course she could. In her master’s program, she studied ways corrosion affects reinforced concrete, and learned to predict the life span of water pipes. Her skills and enthusiasm landed her a job in Los Angeles as a water engineer.

Today, Morales works for the Jacobs Engineering Group, a company with a history near and dear to her heart. In 2017, Jacobs acquired CH2M, an engineering firm known for preventing a huge algae bloom from destroying the beauty of Lake Tahoe, in Morales’ home state of Nevada. Growing up, Morales never realized that the lake she enjoyed every summer was crystal clear because of engineering.

In the late 1960s, CH2M designed the wastewater treatment process for the South Tahoe Water Reclamation Plant. Being the first advanced water treatment system of its kind in the world, the tertiary treatment facility infused lake water with lime, removed ammonia, then filtered water through activated carbon to remove pollutants.

“Knowing it was my company that did this makes me so proud to work at Jacobs,” Morales said.

Recharging the Water Cycle: San Diego

Morales’ current project involves designing yard piping for the Pure Water San Diego program. Currently, San Diego imports up to 85% of its water. As the city’s population grows, so does demand for clean water. The program is designed to increase supply by treating groundwater aquifers and recycling wastewater resources.

When all three phases of the program are completed by 2035, that yard piping will mechanically move 83 million gallons of treated water per day from Pure Water facilities to nearby reservoirs. Phase 1 is scheduled for completion in 2021. “If you think about it, all of our water is recycled,” Morales said. “We’re drinking water that dinosaurs once drank. It’s a precious resource passed through generations, and we need to cherish it.”

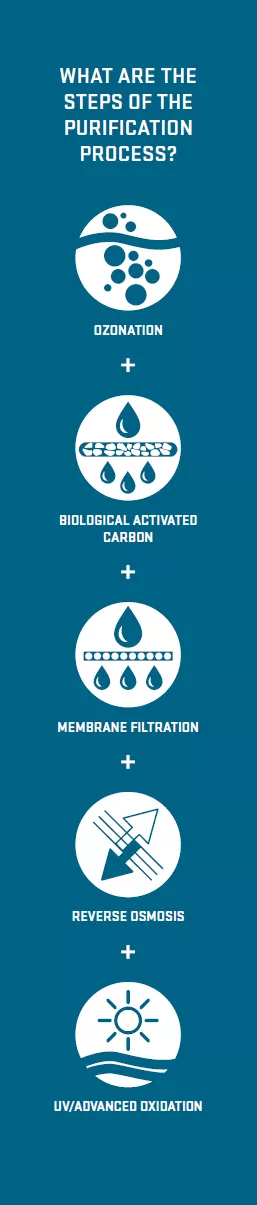

The process of turning wastewater to potable water involves five steps. Ozone is infused into wastewater to break down contaminants. This water is then pushed through biological carbon filters that, when supplied with oxygen, consume up to half of the living organisms present. Next, water is passed through membranes to remove viruses and bacteria. From there, in a process known as reverse osmosis, high-pressure pumps force water molecules through a spiral of membranes to further filter contaminants. At the end of the treatment process, ultraviolet light destroys any lingering microbes.

“During a site visit of the North City Pure Water Facility, I got to taste the water. It was delicious,” Morales said.

The results of the program will provide a third of all of San Diego’s drinking water, an essential boost for a region that only gets about 10 inches of rain per year.

Paul Lee, a civil engineer and volunteer with the American Society of Civil Engineers Los Angeles Younger Member Forum, noted the importance of Morales’ work, especially in California’s arid regions.

“We import almost all our water, leaving ourselves exposed during extended droughts and natural disasters,” Lee said. “This program allows San Diego to diversify its water supply and become more resilient to water shortages.”

This is not a cautionary tale. It’s already happened. In 1991, the San Diego County Water Authority imported all its water from a single source. When a drought hit, that source was forced to cut the city’s supply by 31%. The Pure Water Program will more than cover any deficits caused by drought, increased import costs, climate change, or natural disaster.

Morales noted that Jacobs can build similar water treatment programs, both in the United States and abroad.

“It’s a process currently used in Singapore and would benefit places like Texas or Florida,” she said.

A ‘Statistically Improbable Engineer’ Gives Back

Off the clock, Morales spends a lot of her free time working with the ASCE, talking about engineering with kids. She’s particularly interested in reaching audiences underrepresented in the field.

Monica Morales teaching students

Monica Morales teaches young students about civil engineering during an Engineers Week field trip.

“According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor, out of all working engineers, 14.8% are women and 7.9% are Latino,” Morales said. “I’m a Latina and a first-generation college student. I represent about 1% — a statistically improbable engineer.”

To balance the scales, Morales actively works with young students, especially girls. She serves as chair for two ASCE committees that promote STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) careers to K–12 students. During National Engineers Week every February, Morales can be found participating in hands-on activities with students.

“Dream Big: Engineering Our World” is an IMAX film produced in partnership with the ASCE. It demonstrates how engineering impacts society. Morales organized dozens of free screenings around Los Angeles for underserved kids and school classes.

“In doing so, she has inspired thousands of students to consider engineering,” Lee said. “She really did help to spread the word about the amazing things engineers do.”

Perhaps Morales does this work to right an old wrong.

“I never had the ability to hear from engineers at my school,” Morales said. “I want underserved students to know that if I can do it, they can do it too.”

Ruwanka Purasinghe, past president for the ASCE Los Angeles Younger Member Forum and associate engineer at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, said, “At the female STEM events, Monica proudly wears her hard hat to show the girls that they can be engineers and cool at the same time.”

Morales believes females will fill a significant gap in the field. “Engineers serve a very diverse public. Over half of our population is female. Who better to serve that half?” Her drive stems from her days as a student at Oregon State.

“Every female engineer has faced some backlash in one way or another. We didn’t back down regardless of all the warnings we heard before we committed to an engineering major,” she said.

Engineers Can Help Promote Stem Careers

Morales said others working in STEM fields can give back to their communities the way she has.

“My parents couldn’t prepare me for college, because they didn’t have the opportunity to go themselves. My network at Oregon State provided me with the mentors I needed,” she said. “My mentors at my internships really showed me that civil engineering was my dream job.”

Now, when she speaks to others interested in working with K–12 students, she advises, “Tell them what you wish you’d known when you were their age.”

Epilogue

A couple of years ago, Morales got a phone call from her mother, who had just finished her shift at the blackjack table. She told her daughter that a certain civil engineer had returned to the casino. Instead of dealing a card, she handed him her phone. Morales had the opportunity to thank him for introducing her to a career she loves. Even though the engineer said it was all her mother’s doing, Morales will repay his favor anyway — by providing clean water for thousands of people.

To learn more about Monica Morales and her passion for clean water, see the ASCE’s 2019 Professional New Faces of Civil Engineering video here: https://beav.es/Znc.