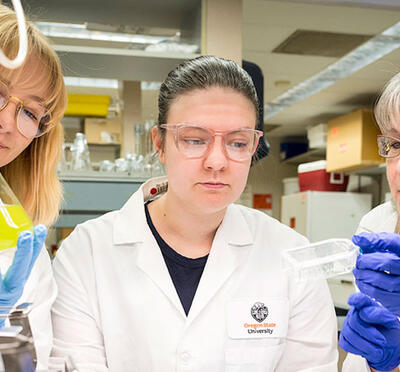

Bahman Abbasi has always been driven to help those in need and protect the environment. As an associate professor of mechanical engineering at OSU-Cascades, he’s doing this by innovating ways to bring clean water to the world.

Abbasi has developed and patented two technologies (U.S. Patent Nos. 11383179 and 11471785) that use the process of humidification-dehumidification, and he and his collaborators are deploying them in two clean-water applications. One is a desalination technology that doesn’t require complex infrastructure or lots of energy, and which is poised to help the world secure more lithium — the increasingly scarce metal used in rechargeable batteries powering everything from ear buds to electric vehicles. The other removes contaminants from water polluted by industrial processes like hydraulic fracturing, mining, and agriculture.

contaminants from drinking water.

Desalination and lithium mining, done differently

Abbasi’s technology eliminates the vast infrastructure of pipes, pressure vessels, and membranes employed in other desalination methods, while reducing the energy that reverse osmosis requires. And it works in a wide range of salinities, from seawater to the less concentrated brines in desert lakes where lithium is found.

“Our technology can be applied at either small or large scales and operates at low temperatures and low pressure, which means we don’t need thick stainless-steel infrastructure or pressure vessels,” Abbasi said. “We use inexpensive, polymer-based materials that can operate with minimal maintenance.”

Conventional desalination systems produce, in addition to clean water, a concentrated brine that can be environmentally damaging when discharged into oceans or lakes.

“Our technology has zero liquid discharge, resulting in only clean water and solid salts,” Abbasi said. “So, we can achieve full desalination, or we can also deploy the technology at existing reverse-osmosis plants to treat the concentrated brine and remove all remaining water. This results in valuable salts that can be sold, instead of putting them back into the environment. In addition to seawater, we can work with domestic continental brines in subsurface lakes, where the solid end-product, in some cases, is very high-value lithium salts.”

Lithium is essential for production of lithium-ion batteries, supplying a global market valued at around $37 billion in 2020 and expected to grow to more than $190 billion over the next five years, according to Fortune Business Insights. Much of the world’s lithium is still hard-rock mined using a highly polluting process. Although the U.S. has about one-tenth of global lithium reserves, most of that metal is dissolved as salts in dilute, continental brine deposits in the Western states.

“If we can concentrate these brines in an environmentally responsible way and extract the lithium, the U.S. can be lithium self-sufficient,” Abbasi says. “Our technology can leave the continental brines, the aquifers, and the landscapes intact and extract the lithium with just about no environmental impact.”

Removing contaminants from industrial water

Abbasi’s second technology removes toxic pollutants from water used in industrial processes — like hydraulic fracturing, which uses as much as 10 barrels of water for every barrel of oil produced. Using Abbasi’s patented three-stage process, that water can be purified and reused.

“There is an immense amount of already contaminated water we can treat and reuse for industrial and agricultural processes, eliminating the need to continually use fresh water,” Abbasi said. “Our goal is to have a closed-loop system that cleans and uses the same industrial water over and over again.”

Fracking is a widely distributed industry, so construction of a treatment facility at each well is not an option. Contaminated water from fracking and mining operations is trucked long distances to be treated, or to be deep-well injected below ground — in states where that is still allowed. But injected wastewater can still potentially contaminate drinking-water aquifers. Abbasi’s technology provides a more economical and environmentally sustainable alternative.

“Our treatment system is containerized, portable, and deployable anywhere you have production of wastewater,” Abbasi said. “And it is powered by energy from flue gases that are normally being flared off and wasted.”

Abbasi joined OSU-Cascades in 2017, after working for General Electric and then as a consultant at the Department of Energy. In 2018, he was awarded $2 million in funding from the DOE for his desalination technology, and a year later another $3 million in ARPA-E funds to advance his wastewater-cleanup technology. His patented technologies have been semifinalists in national competitions, and he has applied for a third patent for related work.

In 2020, Abbasi launched the company Espiku, with a diverse team of collaborators from Oregon State and beyond. The name means “the white mountain” in Luri, the language Abbasi grew up speaking as a child in western Iran, where war made water, food, and energy scarce. That experience is part of the reason Abbasi is driven to ensure the world has enough clean water.

“I started the company specifically to spin out these technologies and make them commercially viable and market-ready,” he said.

Abbasi is very happy to be part of Oregon State. “When I was at the DOE, I worked with dozens of top-tier universities, including Oregon State, so I saw a lot of different cultures,” he said. “I loved the Oregon State culture then, and it’s been exactly as I’d hoped — the collaborative, open-minded, supportive culture here has been a truly decisive part of why I’m able to do this work.”

Season 12 takes us back in time to follow the progress of

a research project to turn salt water into drinking water.

In 2018, Bahman Abbasi,…