OREGON STATE’S ‘ENGINEERING TRIANGLE’

In 2008, 180 acres of Oregon State University’s Corvallis campus was designated a National Historic District. At the time, it included 83 structures, 59 of which are historically significant. One wedge-shaped area in the district’s northeast corner encompasses buildings predominantly related to engineering, physics, and chemistry. Landscape architect Albert Davis Taylor, who updated the campus master plan in 1926 and 1945, dubbed this area the Engineering Triangle.

Five of its buildings have particularly noteworthy histories. Of these, four were designed by Portland architect John V. Bennes, who left a deeper and more enduring impact on Oregon State’s architectural heritage than anyone else. From 1907 through 1941, he designed no fewer than 49 new buildings, major additions, or major renovations on campus. Of the 30 that remain, 24 are in the historic district.

In 1926, Taylor proclaimed: “With the exception of the original college buildings, all of the permanent buildings in the campus development possess a unity of design which is exceptional.” It was unmistakably a nod to Bennes’ harmonious vision and to the Classic Revival style he favored, which dominates Oregon State’s architecture. Bennes may have created the most comprehensive architectural legacy of any college campus in the United States.

Beyond their graceful presence, these five buildings represent the stories of the countless people who have passed through them. The tales that get told and retold through the decades often embody the colorful and vibrant individuals whose names grace their facades, and whose influence — by way of their leadership, imagination, and character — still lingers at Oregon State.

KEARNEY: SUBSTANTIAL AND ELEGANT

Kearney Hall predates Bennes’ campus work. It began as Mechanical Hall, constructed in 1900 at a cost of $25,539.20 (about $700,000 today). The building replaced its namesake predecessor, destroyed by fire two years earlier. An article in the October 1898 Barometer stated: “So fierce was the work of the fire that in four short hours what had so long been known as Mechanical Hall was naught but a heap of smouldering ruins and uncomely walls of charred and crumbled brick.”

The first Mechanical Hall had housed about half the classes of the entire institution, so faculty and administrators scrambled to find any shelter in which to conduct lessons for the college’s 90 engineering students, such as the men’s gymnasium and the armory.

Disaster wasn’t going to strike twice. The State Agricultural College catalog announcements for 1899-1900 declared: “One of the most substantial, as well as elegant, structures on the campus is Mechanical Hall, recently finished. With its solid stone walls and galvanized iron roof, it is constructed as nearly fireproof as modern architecture can make it.”

Though the second iteration was intended primarily as a classroom building for what would become (in 1908) the School of Engineering, other subjects, such as botany, horticulture, mathematics, woodworking, and millinery, were taught there as well.

A third floor was added in 1920, and the building was renamed Apperson Hall. It became Kearney Hall in 2009 after a $12 million makeover, over $4 million of which came from Lee Kearney (’63 B.S., Civil Engineering) and his wife, Connie. “It’s an old building,” Lee Kearney said in 2004. “The floors creaked a lot. It was not a building you thought much about.” The Kearneys wanted to change that. Today, its sparkling interior is the pride of the School of Civil and Construction Engineering, and it’s only the second building on campus to carry a gold LEED certification.

Lee Kearney is the retired president of Kiewit Construction, a subsidiary of Peter Kiewit Sons Inc., one of the largest construction and mining companies in the country. During his 32 years with Kiewit — his entire career — he saw more than 200 Oregon State graduates placed at the company, personally hiring more than 50 of them. He was inducted into Oregon State’s Engineering Hall of Fame in 2001.

MERRYFIELD: MODEST BUILDING, HUGE LEGACY

Merryfield Hall, the first campus building designed by Bennes, went up in 1909. It, too, has lived several lives: as the Mechanical Arts Building, the Industrial Arts Building, and the Production Technology Building. A major renovation was completed in 2020, and Merryfield will now be used for offices for faculty and graduate students from the School of Nuclear Science and Engineering, a general-purpose classroom, office space for the college, and large “innovation spaces” for students to work collaboratively.

But the most memorable thing about the modest, low-slung structure is its namesake, Fred Merryfield, one of Oregon State’s most celebrated alumni and faculty. Born in England in 1900, Merryfield talked his way into the Royal Flying Corps at age 17 and flew fighters during World War I. He was shot down over enemy territory and severely injured, but he made it back to England.

After the war, he struck out for the U.S. with plans to work his way across the country and sail for Australia. He made it as far as Corvallis and Oregon Agricultural College, where he earned a civil engineering degree in 1923, followed by a master’s degree in sanitation engineering on the East Coast. In 1927, he returned to Corvallis and joined the engineering faculty, serving until his retirement in 1966.

During World War II, Merryfield volunteered as a civilian and laid out the sanitation system at Camp Adair, north of Corvallis. It housed approximately 40,000 people — enough to have constituted the second largest city in Oregon. After the fall of Singapore, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and served in New Guinea.

Merryfield, a favorite among students, was a practicing environmentalist long before most people had ever heard the word. In the 1950s, he played a pivotal role in cleaning up the heavily polluted Willamette River. His most enduring legacy is CH2M, the environmental engineering firm that he founded with three former students in 1946 and which grew into a global powerhouse in its field, ultimately to be acquired in 2017 by Jacobs Engineering Group.

BATCHELLER: TRUE TO BENNES’ PLAN

These days, people traveling through Batcheller Hall often mistake it for just a corridor connecting Covell and Dearborn halls. In fact, it stood conspicuously alone as the Mines Building when it was completed in 1913, becoming the first of what would become three interconnected structures at the heart of the engineering campus. A year later, the School of Mines faculty doubled, from three to six. Batcheller has remained true to Bennes’ original plan, changing little since it opened.

The building was renamed in 1965 for James H. Batcheller, aka “Gentleman Jim,” a mining professor and former head of the School of Mines, who was beloved of students and colleagues alike. A noted tinkerer, he converted his car into an early RV for cross-country explorations with his family of six.

During World War I, the School of Mines provided courses for the Student Army Training Corps in the handling and use of explosives. And in 1916, about $600 worth of platinum — more than $14,000 today — was stolen from the school. The culprit was never apprehended, but authorities suspected an “inside job.” The building officially became part of the engineering department when the School of Mines closed in the early 1930s.

GRAF: FROM STEAM ENGINES TO ROBOTICS

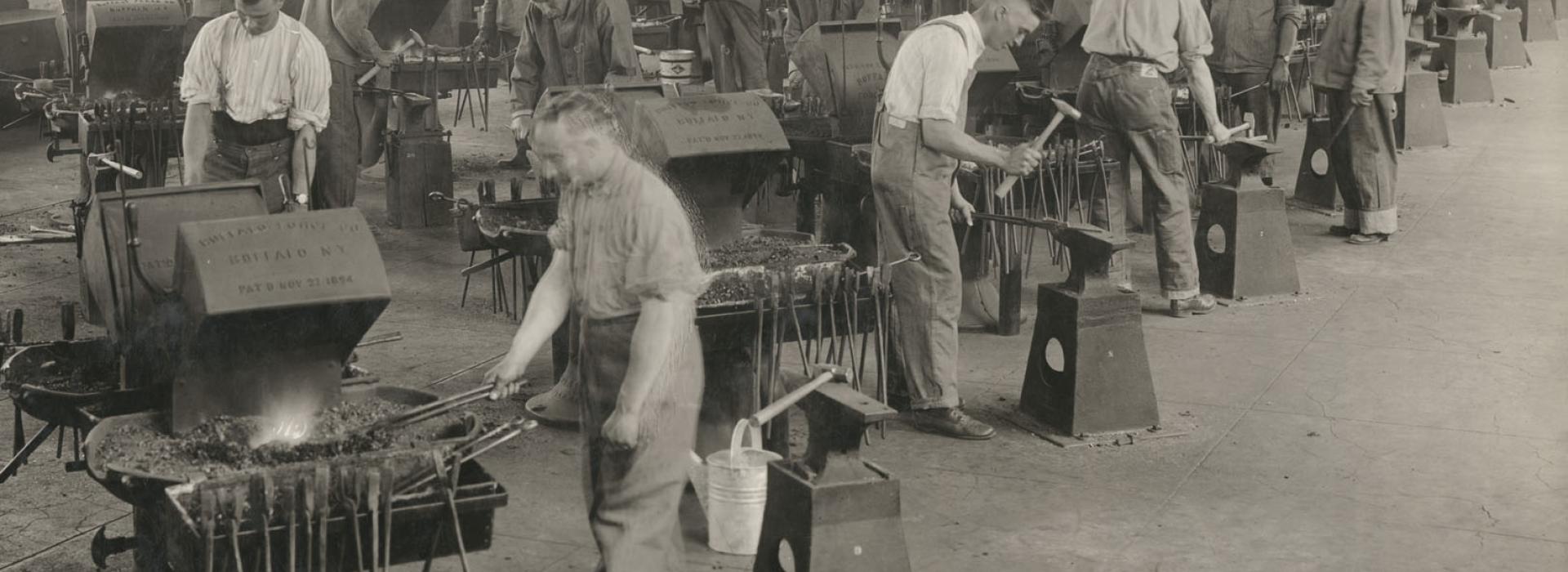

Graf Hall, completed in 1920 as the Engineering Laboratory, is another workhorse of the college. It has housed a materials lab, a hydraulics lab, and a steam and gas engine lab, all served by a 5-ton electric crane. It once contained a colossal, two-story machine nicknamed “the Nutcracker,” which researchers used to test the strength of construction materials.

In 1967, the building was renamed to honor Samuel H. Graf, a 45-year Oregon State faculty member who earned five engineering degrees from the university and held numerous posts over his long career.

In 2015, the college’s burgeoning robotics program consolidated its dispersed labs and faculty in Graf. In preparation for their move-in, the building underwent a $1.3 million renovation. The aging high bay was transformed into a stunning research space, and new offices and conference rooms were installed on the third floor to serve the quickly expanding faculty ranks. A second renovation, which has been in the planning phase for a couple of years, is expected to begin in fiscal year 2021.

COVELL: THE LIVING HEART OF COE

Covell Hall, completed in 1928 at a cost of $177,000 ($2,631,000 today), was originally called the Physics Building. It was later renamed for Grant Adelbert Covell, the first dean of the School of Engineering. He also held the first position devoted exclusively to engineering and formed the Department of Mechanical Engineering. Its first two graduates received their degrees in 1893.

of 1900, circa 1926.

Covell may be the only building on campus where civil defense bomb shelter signs from the Cold War still survive inside. Dozens of similar signs once marked access points to the 37 emergency shelters on campus. High above, volunteers would regularly climb to Covell’s roof and report all aircraft they spotted.

KOAC Radio, a public station, started broadcasting from Covell in 1928. By 1931, it featured 12 hours of daily programming. The station’s call letters still appear prominently on a glass transom on the second floor. In 2009, Oregon Public Broadcasting moved the studio to Portland. It still broadcasts at 550 AM.

Grant A. Covell, nicknamed “The Judge,” was described in the 1926 issue of the OAC Alumnus as “calm-eyed, tall, and magnificent … His smile was a modest denial of all assumption or pretense. It was almost an apology for his dignity … His uncompromising candor; his kindly but unwavering simplicity and directness; and his open-minded breadth of vision have combined to make him a figure of massive and noble proportions on this campus.”

In the same issue, Covell wrote something that applies no less today than it did a century ago — though it could benefit from more inclusive language: “The training of young men to become engineers is more complex and more difficult as civilization advances and extends her boundary farther and farther into the unknown. The profession itself, once so simple, has now become so intricate that no man can master all its details. The best that can be done is to cover a very limited field, and that imperfectly.”