KATELIN GODWIN

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

ECOLOGICAL ENGINEERING STUDENT

Pursuing a degree in ecological engineering — with a minor in environmental engineering — is a natural extension of Katelin Godwin’s upbringing and lifelong awareness of the fragility of the natural world and her sense of obligation to protect it.

“Our household is very science oriented, and living sustainably is just something my family does,” said the fourth-year undergraduate student from Folsom, California. “My parents were great inspirations. My dad, for instance, is a hydrogeologist for California’s Department of Water Resources who works in sustainable groundwater management, so I understand the importance of being diligent stewards of our planet. We can’t just keep using natural resources as if they’re never going to run out.”

During an Advanced Placement environmental science course in high school Godwin first decided she wanted to study environmental engineering and, later, ecological engineering in college. “I liked the idea of applying math and science to mend and preserve the environment,” she said, “and I was attracted to the problem-solving part of engineering. Creating solutions that can lead to a better world was a big reason I wanted to become an engineer.”

Habitat restoration holds a particular fascination for Godwin. Her senior design project involved remediation and restoration of a stream in Scappoose, Oregon. “We were rebuilding a habitat that was harmed by bad forest management practices,” she said, “It wrecked the salmon spawning grounds, which are important for commercial and recreational fishing and which also have tremendous significance to the cultures of indigenous communities. The work was very gratifying, and I felt like we really made a difference.”

The COVID-19 pandemic meant that Godwin’s 2020 internship with Chemica Technologies, a biotechnology company in Portland, had to be done remotely. Her main assignment was to collect information about point-of-use drinking water filters (like Brita filters or under-sink filters).

“It was very helpful for learning to work by myself, and I had to be self-driven and manage my time well,” she said.

The internship also served another important function: It helped Godwin realize that she wasn’t too keen on a career in traditional environmental engineering — work that can include designing wastewater treatment systems and researching the environmental impact of proposed construction projects. What excites her is ecological engineering, in which natural solutions like microbes and native plants are used to remove contaminants from water and to maintain healthy watersheds.

It’s the type of work she can imagine doing throughout her career, whether the work is habitat restoration, sustainable water management, or improving access to clean water for underserved communities.

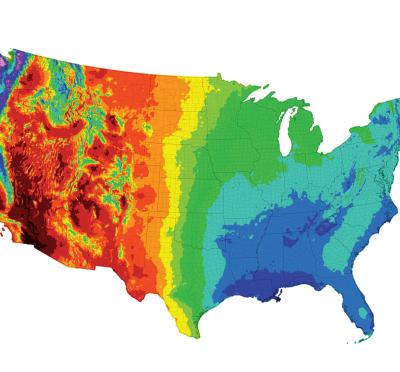

“As the impact of climate change inevitably moves farther north, Oregon is expected to become drier and drier, impacting both the land and Oregonians, so smarter water management will become crucial here,” said Godwin, who recently began a new position as civil staff engineer at RH2 Engineering in Medford, Oregon, a firm that specializes in water resource and municipal engineering in the Pacific Northwest. “How do we create these management solutions so that they maximize protection of the environment and the people who live there?”

Photo Courtesy of Zachary Dunn

ZACHARY DUNN

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE

FOREIGN SERVICE OFFICER

Zachary Dunn grew up in Albany, Oregon, where he excelled at math and physics and loved science. After job shadowing a family friend who was a structural engineer in Corvallis, Dunn thought engineering might be a worthy career to pursue.

“Lo and behold, Oregon State was right next door and had a great engineering program,” he said. “So, it was a natural fit for me. I didn’t even apply to any other universities.”

Dunn had no idea this decision would take him from Albany to Africa, sparking a passion for international development, and ultimately leading to a career with the State Department’s foreign service.

As a sophomore, Dunn joined the Oregon State chapter of Engineers Without Borders. He traveled to Kenya three times to drill wells and build water catchment systems in the isolated village of Lela, where residents previously had to walk long distances to get water.

By the time he graduated with an ecological engineering degree in 2012, Dunn knew he wanted to work in international development. But he also knew firsthand that this would involve more than just technology and engineering.

“In Engineers Without Borders, you’re primarily trying to solve technical problems that are fairly simple, low-tech, and inexpensive,” he said. “But in international development, that work is primarily policy- and politics-driven, and it includes a whole social science aspect. So, there was a shift in my thinking, and I realized that if I wanted to pursue a career in international development, I needed more tools in my toolbox than just engineering.”

Dunn enrolled in Oregon State’s two-year master’s program in public policy. Between his first and second year, he was awarded a Boren Fellowship and returned to Kenya for nine months to do research. Upon completing his master’s degree, his former undergraduate advisor, John Selker, offered him a job with his organization, the Trans-African Hydro-Meteorological Observatory, which is installing a network of weather stations across Africa to improve climate monitoring and agriculture.

After a stint with TAHMO, Dunn worked with the World Bank and USAID before joining the foreign service. He’s been in Costa Rica for two years as a consular officer and looks forward to ongoing diplomacy work. He starts a new position as an economic officer in Bolivia this fall.

“Diplomacy is going to play a critical role in solving some of the most pressing global issues, like the climate crisis,” he said. “And engineers need to have an active voice in that, beyond just the technology. We need to be more directly engaged on the social side of things, including running for public office.”

Dunn connected with Katelin Godwin’s sentiment about wanting to go beyond the role of a traditional environmental engineer, because he has come to appreciate that real, durable solutions to deepening global crises will require social intervention as well as technical innovation.

“I think if the scientific community has made a mistake in this arena, it has been assuming that developing a technical solution to a problem is equivalent to solving that problem,” Dunn said.

“Developing the technical solution is critical, but implementing it requires overcoming the equally if not more difficult problem of social inertia. The tools for solving this problem are very different, and as engineers we may not be accustomed to using them. It starts with voting, but it can’t end there. We engineers have to take an active role in the civic and political discourse of our communities, whether that be supporting organizations working to advance the causes we believe in, or serving in positions of leadership ourselves.