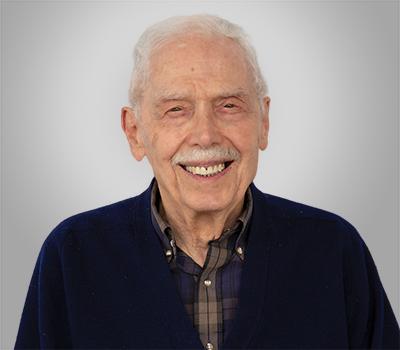

There is no doubt that Gabor Temes feels fortunate to be where he is at. He was 15 years old when World War II came to where he was living in Budapest, Hungary.

“I spent about two or three months in what passed for an air raid shelter and towards the end we had pretty much nothing to eat — we could melt snow for water — but there was no food,” Temes says.

Temes resumed high school after the war and when he finished he was at a crossroads. His mother was hoping he would be a concert violinist, and he had been training since he was 5 years old.

“When I graduated from high school I had to make a decision to become a professional musician or go to university and become something else. And my judgment was that to become a professional musician you had to be really, really, really good and I was only good,” Gabor smiles.

Instead he received degrees in electrical engineering and physics at Technical University and Eötvös University in Budapest and stayed on as a professor until the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Because he and his wife participated in the revolution, they fled the country when the Russians prevailed — which involved a difficult escape to Austria with “fleeting encounters with both Russian and Hungarian border guards and a night in the forest in heavy rain,” Temes says.

A month later they immigrated to Canada where he immediately got a position teaching physics, and later his Ph.D. in electrical engineering from the University of Ottawa. He started out working in industry for Northern Electric R&D Laboratories (now Bell-Northern Research) and Ampex Corporation.

But Temes was drawn to working in academia for the creative freedom and his desire to teach. And then while teaching at UCLA in the 1970s he heard a seminar on a topic that gave him direction for the rest of his career — analog integrated circuits, the interface between the “real” analog world and digital information.

Corvallis — every day rain or shine. And every Saturday his

graduate students join him. It is a time to talk about research

or anything else they want to discuss.

“It’s a beautiful area, because it needs theory and it needs creativity. It’s half engineering and half art,” he says. “Forty years ago people were saying that analog circuits were dead because digital will take over everything — forgetting that digital may take over computation, but the world is still analog. So this translation job needs to become faster and more accurate as digital improves.”

His long career has earned him many accolades including becoming a member of the National Academy of Engineering, and receiving the IEEE Kirchhoff Award, a prestigious distinction recognizing outstanding career achievements. But he is most proud of his many former students, who contributed to the state of engineering art in various important capacities in both industry and academia. He is also delighted to be a part of the analog integrated circuits group at OSU which has become one of the most prominent in the country.

Among engineers Temes has rock star status — visitors to EECS from industry and universities around the world often ask to meet Temes and request he sign one of the several books he has written.

When he is not working he likes to hike in the woods around Corvallis — every day rain or shine. And every Saturday his graduate students join him. It is a time to talk about research or anything else they want to discuss.

Among his good fortunes he counts his two children who are “highly accomplished professionals,” he says. “My wife is also an engineer and neither one of my children is an engineer, and that kind of irritates me,” he laughs, “but they do what they like to do and what they do well.”